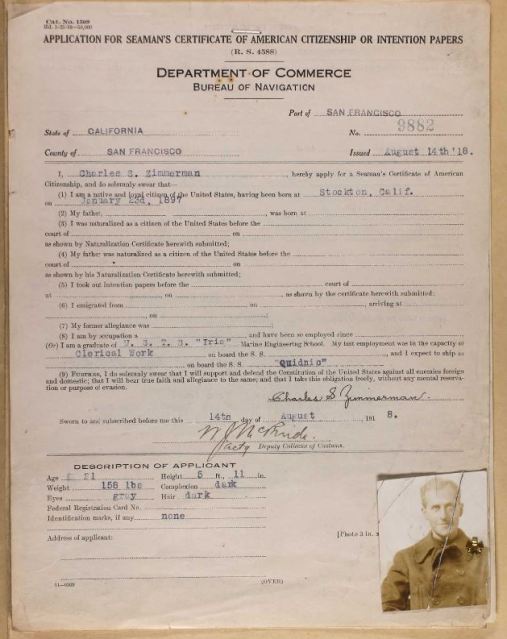

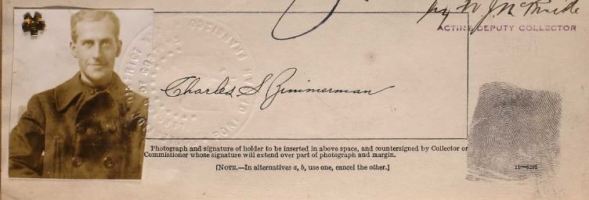

In an earlier post I compared Ancestry’s then new “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939” to draft registrations to answer the question of whether someone who registered for the draft actually went on to serve. I used as an example, the five Zimmerman brothers, who all registered for the draft but didn’t all end up serving. One of those brothers, Charles Stephen Zimmerman, was in training with the Merchant Marines in June 1918 and therefore exempt from military service. In the course of my research into Charles and his Merchant Marine service I came across an unusual and remarkable source. A source which not only gave a physical description of Charles, but also had his thumb print, his signature, date and place of birth and current age, and best of all, his photograph. The source was Charles’ application for a Seaman’s Protection Certificate made on 14 August 1918.1

What are Seaman’s Protection Certificates?

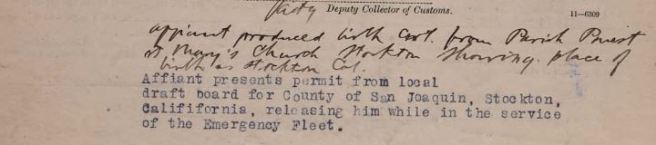

According to NARA (The National Archives and Records Administration) these documents were issued during the late 18th century through the early half of the 20th century, at all U.S. ocean and Great Lakes ports, and served as a seaman’s passport. Those applying had to be United States citizens and had to provide evidence of such in the form of a birth certificate, or an affidavit by a relative or friend, or a citation to naturalization proceedings. 2 Often those documents were appended to the application. In Charles’ case, no other documents are in his file but there is a note indicating he provided his birth certificate, from the parish priest at St. Mary’s church in Stockton, California.

The history of the Seaman’s Protection Certificate

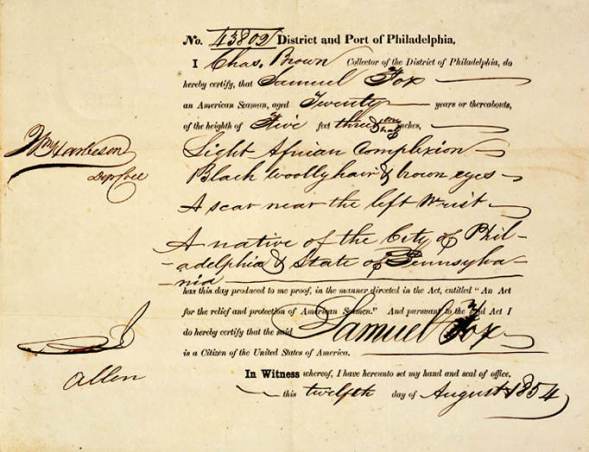

These certificates were first issued to American sailors to prevent them from being impressed into service by British warships in the period leading up to the War of 1812. Impressment was the forced recruitment of men, practiced most often by the British Navy, into service on their ships.

During the years of American slavery, free men of color who were sailors or seamen, were also issued these protection certificates to prove they were not slaves when stopped by officials or slave catchers. Frederick Douglass himself used the ‘protection papers’ of a free man of color, a sailor, to escape: 3

“It was the custom in the State of Maryland to require of the free colored people to have what were called free papers. This instrument they were required to renew very often, and by charging a fee for this writing, considerable sums from time to time were collected by the State. In these papers the name, age, color, height and form of the free man were described, together with any scars or other marks upon his person which could assist in his identification. This device of slaveholding ingenuity, like other devices of wickedness, in some measure defeated itself—since more than one man could be found to answer the same general description. Hence many slaves could escape by impersonating the owner of one set of papers; and this was often done as follows: A slave nearly or sufficiently answering the description set forth in the papers, would borrow or hire them till he could by their means escape to a free state, and then, by mail or otherwise, return them to the owner. The operation was a hazardous one for the lender as well as for the borrower. A failure on the part of the fugitive to send back the papers would imperil his benefactor, and the discovery of the papers in possession of the wrong man would imperil both the fugitive and his friend. It was therefore an act of supreme trust on the part of a freeman of color thus to put in jeopardy his own liberty that another might be free. It was, however, not infrequently bravely done, and was seldom discovered. I was not so fortunate as to sufficiently resemble any of my free acquaintances as to answer the description of their papers. But I had one friend—a sailor—who owned a sailor’s protection, which answered somewhat the purpose of free papers—describing his person and certifying to the fact that he was a free American sailor. The instrument had at its head the American eagle, which at once gave it the appearance of an authorized document. This protection did not, when in my hands, describe its bearer very accurately. Indeed, it called for a man much darker than myself, and close examination of it would have caused my arrest at the start.”

According to an article in Prologue, the magazine of the National Archives, almost a third of applications were for free men of color. 4 African American research can be difficult, these Seaman’s Protection certificates can be great value to those researchers. The Prologue article is excellent and worth reading to get further information on this unusual source.

The use of these certificates as a form of identification went on until just before the Civil War and then was reintroduced for a short period during the World War 1 time frame which is when Charles S. Zimmerman applied for one.

Besides giving Charles’ physical description and date and place of birth, the certificate also indicated where Charles had trained and the ship he was expected to join. For those seamen who were not born in the United States, their certificates may contain information on where and when they were naturalized, including the names of their parents. Those who witnessed the application were sometimes related to the applicant, providing further clues to follow.

Seaman’s Protection Certificates are definitely an unusual source for genealogists, with an interesting history. It’s worth your time to take a look and see if your ancestor may have applied for one. Both Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org have collections of Seaman’s Certificates, search their catalogs using the keyword ‘Seaman’ or ‘Seaman’s Protection’.

This post was written for the 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks challenge from Amy Johnson Crow. Week 38 prompt: Unusual Source

- “U.S., Applications for Seaman’s Protection Certificates, 1916-1940”, database with images, Ancestry.com, (www.ancestry.com : accessed 20 September 2018), application for Charles S. Zimmerman, number 9882; citing NARA; Application for Seaman´s Protection Certificates; NAI: 2788575; Record Group Title: Records of the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation; Record Group Number: 41; Box Number: 112 – San Francisco. ↩

- “Applications for Seaman’s Protection Certificates, 1916-1940”, index, NARA (http://www.catalog.archives.gov : accessed 20 September 2018), Records of the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation, 1774-1982, Record Group: 41. ↩

- Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Hartford, Connecticut : Park Publishing Co., 1882), 223-224; digital images, Archive.org (https://archive.org/details/lifetimesoffrede1882doug : accessed 20 September 2018). ↩

- Ruth Priest Dixon, “Genealogical Fallout from the War of 1812”, Prologue. Spring 1992, Vol. 24, No. 1. National Archives (https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1992/spring/seamans-protection.html : accessed 20 September 2018). ↩

Thank you for sharing this new to me source. Very fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a fascinating resource with an interesting history – I loved the pic of the 1854 one! I had no idea that they existed and I love that people of colour were issued them during the CW period to protect them. I had never heard anything like this!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had no idea of its interesting history either! It’s such a great resource for those conducting African American research who may have had ancestors who were sailors, or who, like Frederick Douglass, used a friends papers to escape. Thanks for stopping by!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating article! I was riveted.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The idea that all who registered may not have served is something I never thought about before now. All of the information provided on these certificates is wonderful. I especially like seeing signatures. It is something personal and unique to the individual, something all their own, yet something we can preserve digitally. Great post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Karenlee! It was such a great moment to see all that information, including a photograph and signature. Thanks for stopping by!

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re welcome. 😀

LikeLike

Very interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person